The Oscars 2018

James Ivory on Sex With Peaches, Oscars, Fighting Harvey Weinstein, and 50 Years of Moviemaking

Website

The Daily Beast

Date:

February 20, 2018

Standing beside his electric typewriter, the screenwriter James Ivory laughed as he recalled what happened when people discovered he was adapting André Aciman’s 2007 novel Call Me by Your Name for the big screen.

“Something everyone said, whether man, woman, gay, straight, was: ‘I hope you’re gonna have that peach scene,’” Ivory said. “‘Don’t tell me you’re going to cut the peach scene.’”

“The peach scene” is the now-infamous moment the sexually and romantically frustrated teenage protagonist Elio has sex with a peach, ejaculating into it.

A reporter asked how Ivory had written and conceived the scene, and what written directions young actor Timothée Chalamet was working from when he had to act it out for director Luca Guadagnino.

Ivory, at 89 the second oldest Oscar contender ever (after director Agnès Varda, also nominated this year), retrieved his original draft. We were speaking at his magnificent home just outside Hudson, New York, two weeks before he won the BAFTA for best adapted screenplay, which bodes well for the Oscars. If he wins, after working on many films that have won or been nominated, it will be his first solo Oscar.

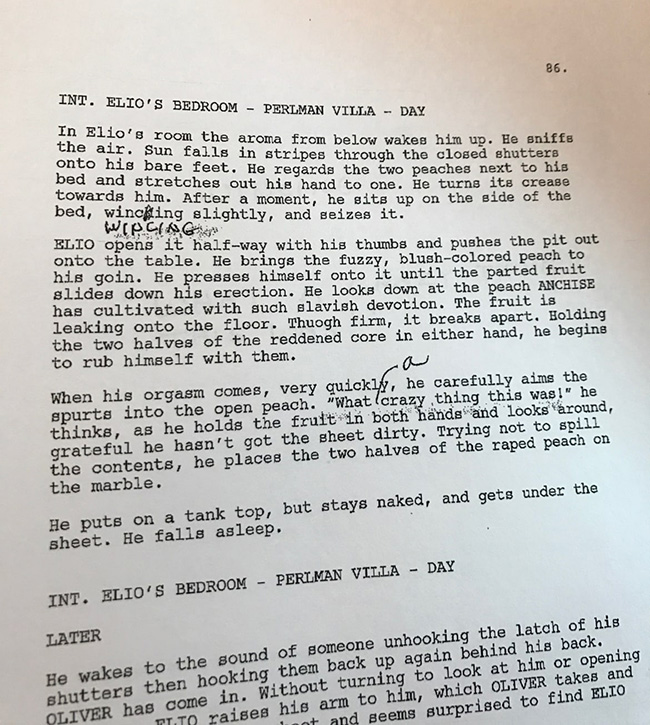

He showed me the script. Ivory writes in sections or portions, so the original Call Me by Your Name script is full of pages of stuck-together paper, a fascinating, multi-layered construct. Ivory sifted through its pages to the peach scene. Here it is. This is how you script-write peach-fucking, and it’s as beautifully phrased as peach-fucking could ever sound.

“I wasn’t there to tell them what to do,” Ivory said of the moment of filming the peach scene. “I more or less described it as best I could. One has to see him assault the peach. I mean, I’ve never made love to a peach. And most peaches aren’t very big, so I wasn’t quite sure you would do that. I was imagining very big peaches.

“I went to Oregon, and found some quite big peaches and thought if the peach was that big you could have sex with it. But I had to see it presented on film to really get it.”

Before the typed version of a script, Ivory writes in longhand on paper and on stiff, white cards he collects from his dry cleaner. If inspiration strikes him late or early, he does this while reclining in a brilliant red bed. He doesn’t type straightaway. He does not want to be constrained by going back to correct errors. Even when he types he has to retype, refine, until he gets whatever it is absolutely right, hence all those stuck-together pages.

Ivory lives in a beautifully restored 6,000-square-foot, 19-room octagonal house, built in 1805 and designed in the Federalist style by architect Pierre Pharoux for lawyer and politician Jacob Rutsen Van Rensselaer.

Ivory’s typing desk is at the back of a huge living room, and to chat we sit in the double parlor overlooking his 50-acre grounds. Coffee table books about Venice, art, and the ancient world sit on the tables. There are various mementos from his travels, like a glass slipper, scattered about signaling a well-traveled, culture-embracing life. He and his life and business partner Ismail Merchant bought the property in 1975. So began a 40-year restoration project, which continued while the property, then split into apartments, still had tenants.

Merchant died in 2005, and Ivory’s friend Jeremiah Rusconi, a local historian who was also art director of Merchant Ivory’s The Europeans (1979), has become his housemate. Ivory broke his leg five years ago, falling on the steps outside the house, and walks with a cane. Keeping the house ship-shape would be too much without help, and he needs and likes Rusconi’s company.

Ivory—“Jim” to his friends, handsome and wry, a precise rather than grandiloquent speaker—still has a flat on New York’s Upper East Side, in a building where he, Merchant, and their close friend Ruth Prawer Jhabvala all lived. Jhabvala screen-wrote most of Merchant Ivory’s 40-plus productions of bonnets, class conflicts, and glossy romance, many of them literary adaptations like the award-garlanded A Room with a View (1985), Howards End (1992), The Bostonians (1984), and The Remains of the Day (1993).

“Love is the absolute basis of my career,” said Ivory, “first with Ismail, then with Ruth.”

It was Ivory, yet to win an Oscar for himself, who co-wrote (with Kit Hesketh-Harvey) Maurice (1987), like Call Me By Your Name, another seminal gay-themed movie about a young man’s homosexuality in the early 1900’s, and the class boundary-defying, sexual norm-defying love he eventually finds with a hot, tousle-haired under-gamekeeper. People still rush up to Ivory on the street to thank him for Maurice, to say how it changed their lives for the better.

The film was released in the midst of an era of extreme homophobia and AIDS panic. For Ivory, it was, like A Room with a View, about young people living their own lives despite the social pressures around them.

If LGBT people are living “truthful lives” today, in 1987, while homosexuality had been decriminalized, many still lived in the closet Ivory said, as well as there being much less acceptance of LGBT people by families, friends, and society at large. “That was why Maurice had value as a movie.”

He is “so happy” that the film means so much to so many.

“This may sound corny, but I’ve always liked to make things that were beautiful,” Ivory said. “I wanted to create beauty. That was my main desire. I’m just glad those films have been found beautiful by many, many people. Political consequences have never really come into my thinking. I didn’t think about it when we made Maurice or when I said first I would co-direct and then write the screenplay of Call Me. I was just making something I thought I would enjoy creating.”

People, especially gay men of all ages, recognize Ivory, and thank him for Maurice regularly. “I was in New York one day, and this guy ran off a bus, grabbed me, and told me that Maurice had changed his life. I’ve also had it many, many times in England.”

Ivory would like to win the Oscar for Call Me, of course, but he doesn’t like to think about it. “You hope the movie is liked and the movie will have a distributor and an audience. That’s all you want. You don’t think of awards and things.”

He recalled being “astonished” when Merchant Ivory movies received their first nominations in costume and acting categories, until A Room with a View scored eight nominations. “We had had successes before, but not on that scale of international success before.”

Ivory only felt competitive at the Oscars once, when Howards End was up against Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven. “I thought we had a very good film, and I didn’t think Unforgiven was all that interesting. I thought we ought to win, and we didn’t.” After that, The Remains of the Day was up against Schindler’s List: another bad night for Merchant Ivory.

“After that, I never got nominated again until now,” said Ivory. Even then, he added, “If you’re the writer you don’t own the screenplay, because it’s so dependent on the good sense and taste of the director. You cannot think of yourself as the owner of the screenplay, you just can’t.”

This year, he likes some of Call Me’s competitors a lot, namechecking Phantom Thread, The Shape of Water, and The Florida Project. Ivory was originally due to co-direct Call Me alongside Guadagnino, but ultimately just wrote the screenplay.

Recently, Guadagnino signaled his desire to write a Call Me sequel. In a later email to me, Ivory writes: “Well, good luck to him! My own experiences with sequels were unhappy: We wanted to do a sequel to Shakespeare Wallah (1965), set in England, entitled A Lovely World, but did not have a happy time with it, and gave it up after two or three years.”

Would Ivory write a Call Me sequel if he was asked?

“I don’t know. It would depend on how André Aciman weighed in, if he did, and what he would write. It’s his creation after all.”

Ivory’s next chance to direct will come with an upcoming project, an adaptation of Peter Cameron’s Coral Glynn, set in 1950s England.

This will be his second Cameron adaptation after The City of Your Final Destination (2009), and will be notable because he revealed that he intends to cast the stars of A Room with a View, reuniting Helena Bonham Carter, Julian Sands, and Rupert Graves (“They’re terrific in their fifties, they all look great and I thought it would be fun to do”). He also intends to tempt Daniel Day-Lewis out of his alleged retirement. This Ivory will write and direct: “I just want to make it totally my film.”

He is also still working on his adaptation of Shakespeare’s Richard II, starring Tom Hiddleston and Damian Lewis as the two kings Richard and Henry V. The latter has been so many years in gestation “it has taken a lot out of me. It is not an epic play. I’ve had to invent a battle scene.” He also wants to shoot it in 3-D.

When I asked about any other projects he’d like to do, Ivory smiled. “No. Let’s be realistic. How long can I be doing this? I don’t know. Let’s see. Physically I’m in good shape.”

So he’ll die working at his electronic typewriter? “Why not?”

Known as the second oldest Oscar competitor amuses him. “Long after Call Me is dust, long after all of my films are dust, that could be what I am remembered as.” Ivory laughed. “That’s what it boils down to.”

When I mentioned to a friend I was interviewing Ivory, the friend said, “He’s British, right?”

“They might very well assume that, our most famous films are English,” Ivory said, smiling, referring to the Merchant Ivory cavalcade of Brit poshos taking tea and muddling and meddling in matters of the upper class heart.

In fact, Ivory is American. He was born in Berkeley, California, the family moving to Oregon when he was 4, and where he went to university. He still has a cabin in the state at a lake where the family holidayed when he was a child.

Growing up, alongside his younger sister Charlotte (who went on to become an art teacher), he didn’t like team sports, but loved swimming and water skiing. He immersed himself in history and art, and “little projects” borne from that. He started to read adult novels when he was 12, particularly books about the Old South (his mother was from Louisiana), alongside films like Gone with the Wind (1939).

“I was always able to go to the movies. I remember the Popeye show every Saturday morning. The Lone Ranger. Hopalong Cassidy. I wanted to see films constantly, and did—big splashy ones like The Wizard of Oz (1939). I loved John Ford’s Drums Along the Mohawk (1939), and remember being affected by The Grapes of Wrath (1940), Tobacco Road (1941), and Swiss Family Robinson (the 1940 version). I remember being 7 or 8, and being carried out of Gunga Din (1939) by my mother because she thought it was too violent.” He paused and smiled. “That was the only film I was ever removed from.”

Ivory’s sister became an alcoholic when she was quite young, “maybe in the last year of high school.”

At Mass one morning, she was kneeling in the pew during Communion, and she had passed out. Their father noticed, and calmly dealt with the situation without causing a ruckus. “He was the soul of carefulness and sensitivity, that was the kind of person he was.” (His sister, as an adult, attended AA, received the help she needed, and was a loving parent to her children.)

Ivory’s father owned a lumber company. In World War I he had been a cavalry soldier in France, and Ivory wonders if he became a Francophile because of that. His mother also had French roots. His father’s father had come from Ireland and been a labor leader, leading strikes in upstate New York; his mother’s father was a riverboat gambler “who was meant to have been incredibly handsome.”

As a child, Ivory was “very imaginative.” He asked for guidance from an architect working on the family home, who advised him to go to architecture school, which he did. Fascinated by movie sets, Ivory visited movie studios when he was “12, 13, or 14. We sold lumber to MGM. I would look very critically at sets. I went on one set and saw the rug was inappropriate. How could I know at 12, 13, 14?” He laughed.

I asked what was wrong with the rug. “It was a boring tan color.”

Ivory’s parents’ marriage was happy, and Ivory’s impetus to strike out on his own was to extricate himself from the Catholic Church.

“Friends at college would say to me, ‘Jim, you can’t believe in all this stuff.’ His father was not judgmental (“he was the kind of Catholic like President Kennedy: He would go to Confession and Communion twice a year at Christmas and Easter”), nor was his mother, but neither knew Ivory was gay.

“It would have been impossible for them to speak about it. They must have thought, ‘Who are his girlfriends, and will he get married?”

Later in life, his father met Merchant; the trio even traveled together to Rome and Venice with Ivory and Merchant sharing a room. “He said nothing.” Did Ivory ever want to come out to his parents? “No. I didn’t want to make then unhappy, and it would have made them unhappy in those days. It was so unbelievably… it was an unspeakable thing back then. Later in her life my mother was not in good health and I was not about to add that to her problems.”

Of course in Call Me, there is Michael Stuhlbarg’s amazing speech as Elio’s father to his son at the end of the movie, about Elio following his heart and experiencing all life has to offer. It is an implicit, heartfelt embrace of his son’s sexuality without mentioning it.

“I don’t think my father would have been able to speak of such things,” said Ivory. “It was very difficult for my father to speak of anything emotional without tearing up. He would say the strangest things sometimes. When I was getting ready to go into the army for basic training, he came into my room and sat on my bed, obviously troubled.

“He said, ‘You know when go into army you’ll be with a great many young men. You will be naked and they will be naked, and you are circumcised. Many of the other men will not be, and I do not want you to think you are Jewish.”

Ivory paused. “Isn’t that amazing? This was when I was 24. I said, ‘Well Dad, I have a lot of friends who aren’t Jewish but who are certainly circumcised.’ It was comical but extremely touching.”

When Ivory was drafted he was stationed in Germany, and “loved” playing the impresario, overseeing the performances and travel arrangements of those starring in the soldier shows.

He eventually studied filmmaking at the University of Southern California. His first film was about Indian miniatures, which led to commission to go to India to make another film and which led to his lifelong love affair with the country.

Merchant was another “powerful engine” that changed Ivory’s life. “I can’t imagine…” he began to say when talking about the impact of their meeting had been. “I feel I would not have had the started up in quite the same way without Ismail. He was a powerful producer to have behind you all those years.” With Jhabvala adapting her own novel, the first Merchant Ivory movie was The Householder (1963).

Merchant and Ivory were in both a close personal and professional relationship for over 40 years. The personal relationship became open after a period of time. Ivory had a long-term relationship with one friend, himself married to a woman, for many years who he asked me not to name.

“He was a very highly sexed guy,” recalled Ivory. “He certainly adored his wife and had kids, but one day I got a letter from him. He wrote a lot of letters that tended towards stuff about male physicality. One day he wrote, ‘I’m in love with you, I’ve always loved you, I’ve always desired you, let’s get together.’ So we did.’”

Was it as good as Ivory hoped?

“Oh yes, oh yeah.”

They were lovers for 40 years. Merchant understood, and also had long-term lovers in the side, “and anyone was long-term eventually had to come into the company and make themselves useful,” said Ivory. (Rusconi was a Bafta-nominated art director on two Merchant Ivory films, and once had an intimate relationship with Ivory.)

Coming to terms with being gay was not difficult for Ivory. “It never was. It was not something I wanted to tell everybody, I realized I’d have to be careful about it, but it never struck me as wrong. Though I knew it was against Catholic teaching, all sex outside marriage was against Catholic teaching. We were told if we had sex it was wrong, it was a sin. But I thought, ‘If I’m doing it, it can’t be that wrong because I am a good person, not a sinner. If I am doing it it must be OK.’” Ivory smiled. “As someone pointed out later, that’s also the attitude of a serial killer.

“I never felt any guilt about it. I knew from the age of 12 or 13 I liked boys and didn’t like girls. I had liked girls much younger. I was very much involved in sexual carryings-on as a little boy of 7 and 8, playing doctor.”

Realizing he liked other boys coincided with Ivory going to public school (from parochial school). After his first sex with a college roommate in his final year, Ivory had sex “all the time, and as much as possible.”

Ivory met Merchant (who had come to the U.S. to study in New York in 1958) in 1961, and says he is cautious about talking about their relationship because of Merchant’s still-living, devout Muslim relations in India.

“Forty-four years together is an incredibly long time, the same as being married,” said Ivory. “I think of people who are married and had 40-50 years of a wife or husband and I think, ‘Well, so did I.’”

Did he miss being officially married, as same-sex couples can now? “I wouldn’t have wanted to marry in those days. The idea would seem strange to me and also unnecessary. We were two absolutely devoted people doing what we wanted to do, which was to make films and we were completely loyal to each other.

“We were completely, totally committed to what we did and what we were making, to Merchant Ivory films, to each other, to Ruth, to our world. I don’t see how any marriage could be stronger than that.”

Their third film, The Guru (1969), was a proper studio picture. “We were treated royally. I was put up in the Savoy Hotel. After A Room with a View and Howards End we were allowed to be with the big boys. I learned a few tricks. I learned how to deal with them. I am very rare, in that I always had say over the final cut (apart from one film). Nobody ever tried to come and mess around with what I was trying to do.”

Ivory and Merchant once dramatically clashed with Harvey Weinstein. “He wanted to mess up Mr. and Mrs. Bridge (1990), and Paul Newman, who was the star, said, ‘If you want me to do press, you’re not touching that movie.”

His and Merchant’s experience of Weinstein “was what everyone has said. We had no idea about his encounters with women. He was a brute just to deal with. We had a big fight with him at some point. It was a meeting about how Mr. and Mrs. Bridge should be publicized. He said something and Ismail got very angry, and jumped up and said it wouldn’t be like that. Then I think Ismail challenged him to a duel. There was a cornucopia on the table full of delicious treats, little pastries and cherries. Through all of it, I kept on eating them.

“Harvey and Ismail were supposedly going to go out and fight in the street. Ismail said he was going to beat him up. Ismail took his briefcase as he was leaving the office and smashed it against a glass partition which crashed to the ground. He left me behind. They didn’t fight in the end, but that wall was destroyed.

“Then there was The Golden Bowl (2000), and Harvey again wanted to horribly mess it up, to make cuts and change things. I had final cut say and he couldn’t do it, and so Harvey, who was distributing it said, ‘OK, it’s not going to come out in theaters, it will just go out on TV.”

Ivory said he and Merchant successfully called Weinstein’s bluff on that threat, and then bought the film back from him and sold it to Lionsgate, “who were so cheap they used some of Harvey’s own publicity he had done for the film.”

I asked how Merchant and Ivory didn’t drive each other bonkers working and being together 24 hours a day?

Ivory laughed. That’s why they had separate apartments in New York, he said; they fought a lot, and irritated each other. Merchant’s dominion was the financial affairs of the company, and sometimes Ivory felt he had to intercede on an employee’s behalf who felt they were not being paid properly. But the rows were never relationship-ending; their professional and personal commitment stayed strong.

When Merchant died, “at first, it was truly was the worst thing that ever happened to me,” said Ivory. “Nothing will ever, ever compare to that. In a way his death was unnecessary, but in a way he brought it on himself.”

Merchant, said Ivory, became hypochondriac after breaking his ankle. It healed, but Merchant began having all kinds of fears about his health.

“He would go to see quacks, take prescriptions that were probably not good for him.” He had bleeding ulcers in his stomach, and then got a third one which was almost impossible to see and treat, said Ivory, which led to his death.

For Ivory, to die in such a manner “in this day and age is somehow not legitimate.” It had seemed as if Merchant was going to be alright. They had planned to return to New York, “and then the last time I saw him was when I helped push his bed into intensive care.”

The couple were editing The White Countess (2005) at the time, and Ivory threw himself into completing it after Merchant died. “It was a terrible time, but I did it. Luckily I had that work to do. If I hadn’t had that work to do I would have gotten extremely depressed. I was depressed obviously, but I had to be there every single day and carrying on was probably a good thing.” Friends made sure Ivory wasn’t alone, and he “gradually recovered.”

Next, he made The City of Your Final Destination, starring Anthony Hopkins, Laura Linney, Charlotte Gainsbourg, and Omar Metwally), “which we didn’t have enough money to make. We made it on credit cards. Ismail would never have agreed to that. That film brought me back a bit. I was shooting a film, doing what I was supposed to do. That gave me happiness. I wondered when I would feel joy again, and I did feel joy when I did the music for that movie with Jorge Drexler.”

As Ivory and I sat talking, light leaked from the day outside. We ended up sitting in shadowy darkness. Ivory got up to make a fire, and turn on some lights. He made a delicious pot of Earl Grey tea, and we nibbled on fancy chocolates.

When it came to adapting Call Me, Ivory said he’d cut the reunion scene in the book, and he trimmed down Stuhlbarg’s stirring end speech feeling audiences would not want a long dialogue scene so close to the end of the movie.

In Call Me, Ivory’s only regret is that the love-making scene between the two male lovers isn’t more graphic. “Without showing nudity, I had written it in a way to make it stronger.”

Armie Hammer’s part was originally to be played by Shia LaBeouf, and Greta Scacchi was to play the mother. LaBeouf would have played the older academic as a diamond in the rough, said Ivory, and read with Chalamet. “Luca and I loved it. They had great chemistry. Armie does too. You can really understand the attraction between the two of them.”

Ivory doesn’t have an issue with straight actors playing gay. In Maurice, “they really went for it” (James Wilby, Rupert Graves, and Hugh Grant). But in Heights (2005) James Marsden and Jesse Bradford are supposed to throw themselves on each other in the final scenes and they couldn’t do it.”

It’s rare Ivory doesn’t like an actor; an exception was Raquel Welch in The Wild Party (1975). “She was a nightmare. She didn’t like me. At one point she left the film and had to be forced to come back. Rita Tushingham (in The Guru) was difficult to work with. Kris Kristofferson (in A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries, 1998) was great. What a gentleman.”

He fell out with Dame Judi Dench, after advising her to turn her A Room with a View character, Eleanor Lavish, Scottish. “I think she thought, ‘How dare this American tell me anything about accents.’ She told me my idea was all wrong, impossible. I felt she was a little too ‘on’ during that film. It was a little hard to tone her down and I couldn’t tone her down.”

The final straw came when Ivory cut one of Dame Judi’s scenes from the final film. “She never forgave me or wanted to speak to me again, or have anything to do with me. I once went backstage to see Maggie [Smith] in Lettice and Lovage in the West End. They were sitting there together backstage. I said, ‘Oh hi Maggie, how are you, and Judi was so cold.”

Mr. and Mrs. Bridge and Soldier’s Daughter are his favorite films as they are the most autobiographically connected to him. In the latter, Anthony Roth Constanzo whose character Francis Fortescue becomes an opera star “is really playing me, but I didn’t tell him he was. He’s 14/15, a bit sassy, and in an imaginary world of his own.”

Ivory is protective of the 40-plus films Merchant Ivory produced: They became their own brand—posh Brits gallivanting around in bonnets, and plotting and romancing in grand houses—and that brand and accompanying stereotypes was used to deride Merchant Ivory as much as it was to lionize them.

Merchant Ivory became both noun and adjective, describing just via its name the kinds of films the company made.

“It depends how they treated that adjective and noun which was not always positively,” said Ivory. “They tried to put thus into this ‘heritage’ slot. How dare they. Whose heritage? Ismail was Indian, I’m American, Ruth was a European Jew. We didn’t have the intention of creating an English heritage thing, and didn’t want to be grouped into that sort of thing. Sometimes we threw up our hands.”

Did the trio chat about ditching all the parasols? “No, we did what we liked. I don’t think we ever tailored anything according to what might be written about it.”

So, to his critics who call the movies classist, too lush, too pretty, too about the finer things, and romanticizing a Britain now long gone, what would he say? “That’s their business, not our business,” Ivory said briskly. “That was not our intention. We adapted books by authors like Henry James, E.M. Forster, and [Kazuo] Ishiguro: They were intensely character driven and intensely psychological stories about social nuances of one kind or other, and about the class system.

“That is the heart of those novels. People should think about that, not about curtains and hoop skirts. They should be listening to what was said and done in bearing to important things like society, class, and love.”

Did Ivory feel Merchant Ivory films were misread, then?

“Constantly, of course, and deliberately. I felt they were fed up with our doing all this and wish we would go away. And we did go away after The Remains of the Day, except for The Golden Bowl, and that was about very rich Americans parasitically living off the culture of England and Europe.”

Most of the films Merchant directed (with the exception of The Proprietor, starring Jeanne Moreau), noted Ivory, were about poor and suffering people trying to better themselves.

Ivory misses both Merchant and Jhabvala. “There’s always something. I dream about Ismail a lot, very often. It’s repetitive. I’m usually in some foreign country, and I can’t reach him or he doesn’t want to talk about something. It’s an absence-type dream.” Ivory has not missed companionship since Merchant’s death. “Not in that way. Not really. I wanted to go on making my movies, but no I wasn’t searching for anyone else.”

Ivory said Merchant would be pleased that the Merchant Ivory films are being restored and re-released.

The handsome Rusconi appeared, and talked about the restoration of the house which he has helped steer. He and Ivory guided me around this beautiful house, including showing me the room Jhabvala and her husband always stayed in, kept as it was when she was alive, and Ivory’s brilliant red bed where he sits and writes late into the night. There is a little nest of the stiff pieces of dry cleaner board, ready for a late night or early morning noodling.

Ivory declined to be photographed on the bed. “I’m not sure I know you well enough for that just yet,” he said, as crisply arch as the best Merchant Ivory character.

Instead, I took Ivory’s photograph as he tapped away at the electric typewriter. I assumed he was merely imitating the screenwriter’s art for the camera. But no, after a few minutes of picture-taking, he stood and handed me a piece of paper, signed and dated and with five lines of text typed on it:

All About Eve – Sunset Boulevard – two films from my last year in college – 1951, over which my intellectual friends and I talked. Which – in terms of cinematic art was better? My friends thought “All About Eve,” but I held out for “Sunset Boulevard”. Now I might reverse them.

That little boy who passionately loved the movies became a man who felt passionately the same. Lucky us, right down to the last, beautifully described sacrificial peach.